Implementing Clean Architecture — The Use Cases

Here we present what code hotspots, user-centered design, and the screaming architecture have in common.

We can still hear the echoes of Steve Ballmer’s “developers, developers, developers” chant. This could just be a funny video but even today, software development is too centered on developers. We should shout “users, users, users!” instead.

What can we do about it?

The user-centered design process advocates for close collaboration with users and all we do as a team should be in line with it. For example, you should avoid tech stories on a team’s board and focus on real user stories instead. What about codebases?

The Threat of Technology

Technology is a detail. It’s pervasive and can hinder your codebase. However, many of us are technology evangelists so it’s very easy to fall into that trap on a new project. Fast forward a few months and all you see in a codebase are HTTP filters, queues, JSON, command handlers, SQL, etc.

When browsing a codebase folder structure and reading the code itself, you should be able to quickly scan what it is capable of, without caring too much about frameworks and technologies (how). There should be a hard line splitting technical things (like I/O, web, databases, queues) and the business domain — these should live in different levels of abstraction. Using a domain-driven architecture (like the hexagonal architecture or the clean architecture) is a safe bet in that regard.

Now look at your code, take a step back, and think about how you can make technology just a detail. Don’t let it take control of your codebase. Push it to the boundaries.

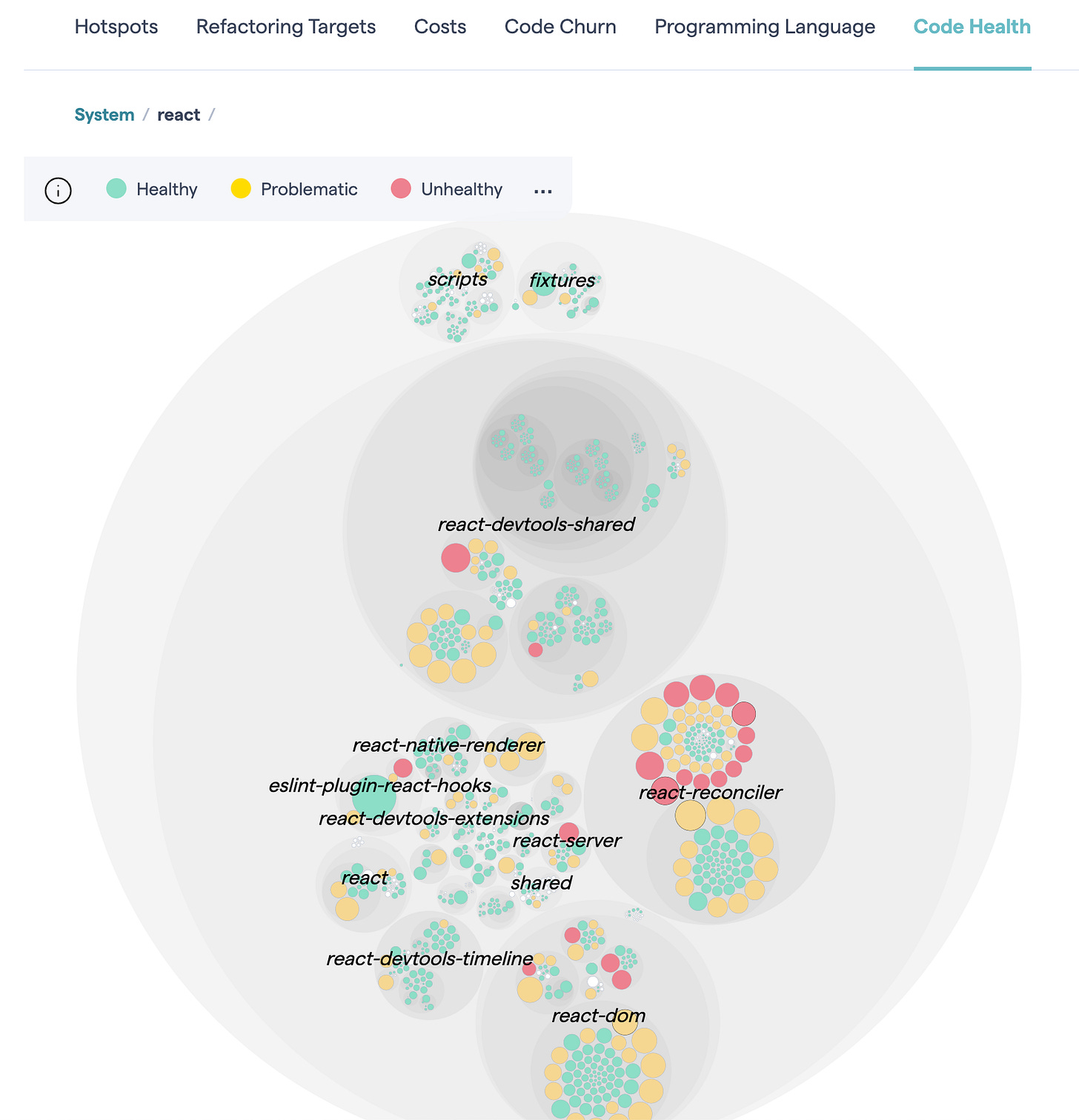

Code Hotspots

Even if technology is split apart from domain code, some codebases still hardly speak for themselves. A typical reason is that they contain huge files with web handlers and others full of business logic. These are called code hotspots. Most of them are god objects (over-busy objects), as they are filled with unrelated functionality, show low cohesion, and clearly violate the single-responsibility principle.

Why is this bad?

Hindered developer experience. Can you quickly find the required feature in huge “hubs” and “services”? Code hotspots grow arbitrarily in size. All you can do is use the editor’s find tool. This negatively contributes to self-documenting code. Also, code hotspots are a common source of merge conflicts as they have lots of reasons for change. Thereby, they create some fear of change, even with tests.

Promiscuous sharing of code. There are two categories of decoupling: vertical, which represents the decoupling between layers (e.g. between domain and adapters), and horizontal, which aims to decouple distinct features. This type doesn’t get enough attention and we end up with features coupled by shared code.

Messy dependency injection. Injecting many dependencies into a hotspot but only needing one or two in each method signals low cohesion, one of the characteristics of code hotspots. This makes tests overly verbose since they end up crowded with dummy mocks.

Uses Cases as the Units of Work

A use case (in particular, a system use case) represents a single interaction with a system. To express intent, its name should start with a verb (e.g. “list movements,” “withdraw money,” “delete my data,” “pay shopping cart”). In practice, a use case is just a function (a query or a command) that should ideally be pure — deterministic and without side effects. Side effects are supposed to be delegated.

A use case is like an algorithm to accomplish a client-driven task. (Clean Architecture for the rest of us)

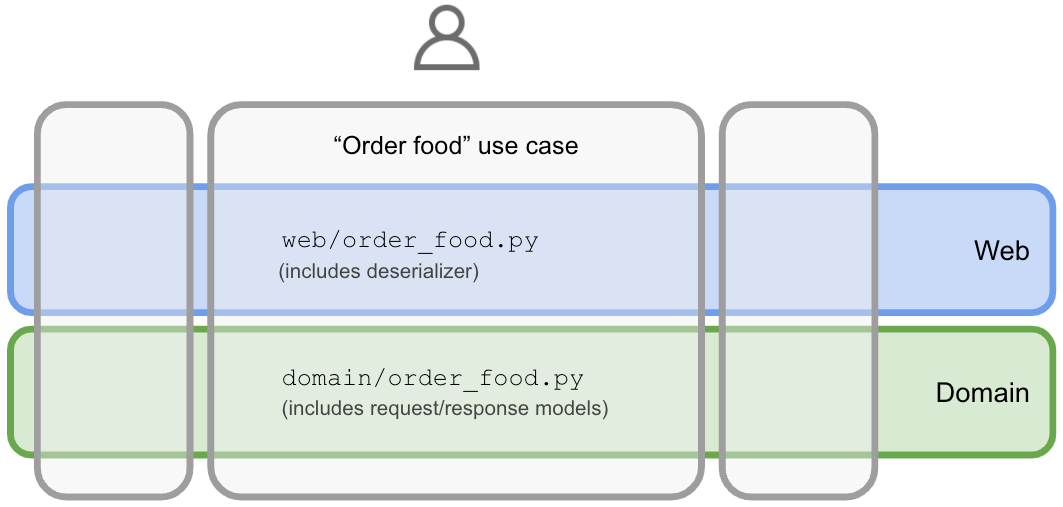

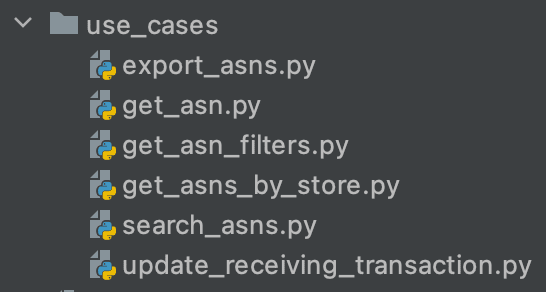

If big files are a problem, splitting is the solution. How? You need a heuristic to split. Splitting by use case is the solution, as use cases are your app’s unit of work (i.e. its architectural atomic device). They should be first-class citizens so that an app’s goals become immediately clear when browsing its codebase. Although this concerns code organization, it ends up encouraging the good practices of a domain-driven architecture.

Let’s consider a backend app served through a web API as an example.

The Web Handlers

In a domain-driven architecture, a web API is a primary adapter comprised of web request handlers (an adapter is an app entry point and contains no business logic).

In a use case-driven approach, each web handler is merely a use case entry point — they have a one-to-one relationship. Therefore, each web handler should have its own implementation file containing validation, parsing, (de)serialization, calling the domain, error handling, response preparation, API docs (e.g. OpenAPI), constants, etc. There’s no other place to look. It’s all there, in one place. Here’s an example (in Kotlin):

class CreateUserHandler(

private val createUser: CreateUser,

) : Handler {

override fun handle(ctx: Context) {

val createUserResult = createUser(

ctx.bodyAsClass(CreateUser.CreateUserRequest::class.java)

)

ctx.status(

when (createUserResult) {

NewUser -> HttpStatus.CREATED_201

UserAlreadyExists -> HttpStatus.CONFLICT_409

}

)

}

}We could apply the same approach to any other entry point of your app (e.g. message broker handlers, web page controllers).

The Domain

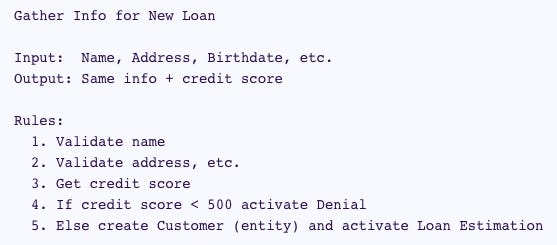

The domain is where the business actions happen. “Service”/“Hub” files full of domain operations are a bad idea. Instead, create a file per use case and name it accordingly. A file with a single public function supporting a use case is not a bad thing. In fact, it’s an excellent idea as it’s modular and cohesive. It should be self-contained and only rely on secondary adapters to meet its needs (e.g. a repository). That said, besides the actual use case function (which includes semantic validation, orchestration,…), include its request/response models, errors/exceptions, and any private helpers in the same file. Here’s an example (in Kotlin); notice the injection of a non-deterministic function to keep the use case pure:

class CreateUser(

private val userRepo: UserRepository,

private val generateUserId: () -> UserId,

) {

operator fun invoke(createUserRequest: CreateUserRequest) = userRepo.save(

User(

id = generateUserId(),

email = createUserRequest.email.toEmail(),

name = createUserRequest.name,

password = createUserRequest.password.toPassword(),

)

)

data class CreateUserRequest(

val email: String,

val name: String,

val password: String

)

}The Tests

Create a test file per use case. Each test file exercises all scenarios of a use case. It also only needs to inject the use case actual dependencies rather than a bunch of them. These factors contribute to “tests as documentation” — one of the goals of automated testing — because they help to describe the use case as a user/client.

Use cases are your units to be tested. With this approach, you have a clear testing surface: the use case directly or indirectly (through the web handler). Don’t create any other kinds of tests (e.g. serializer tests).

You can test the use case directly or through the web handler (more realistic). That depends upon your testing strategy.

It’s important to acknowledge that a testing strategy is always a trade-off, so let’s talk about the pros and cons:

✅ It makes your tests decoupled from implementation details (black-box testing), therefore, supporting smooth refactorings.

✅ It tests the SUT in a more realistic way since it’s an outside-in approach. This also improves code as documentation.

✅ It reduces the number of tests to functionality that’s indirectly tested in the Arrange and Assert parts of tests.

? The ability to quickly pinpoint issues is penalized as there is more code being covered per test.

? Tests may become slower if you abuse real databases or other I/O.

In our case, the trade-off is positive, but it’s important to put this in perspective in each project.

Advantages

Small files that share no code are the main enablers of a use case-driven approach. There’s a cumulative price to pay for huge files that are often changed. It’s much easier to reason about small self-contained files. Duplication is not a problem. Eventual similarities are only illusions as use cases will grow in different directions. There’s no need to share serializers, exceptions, DTOs, and other details; just put them in their use case (make them private if possible).

How do codebases cope with a growing number of features? The presented strategy is a great tool in that regard. We tried it in a project at NewStore. Here’s what we observed.

Developer Experience

It greatly contributed to an improved developer experience:

Since we knew there was no code sharing between features, we felt at ease and more efficient changing code as the blast radius was always small and easily identifiable;

For compiled languages, the IDE was faster when analyzing a file and when executing automated refactorings;

Having only one reason to change a file reduced merge conflicts;

Files were smaller— we barely needed to use scroll because they only contained the use case code;

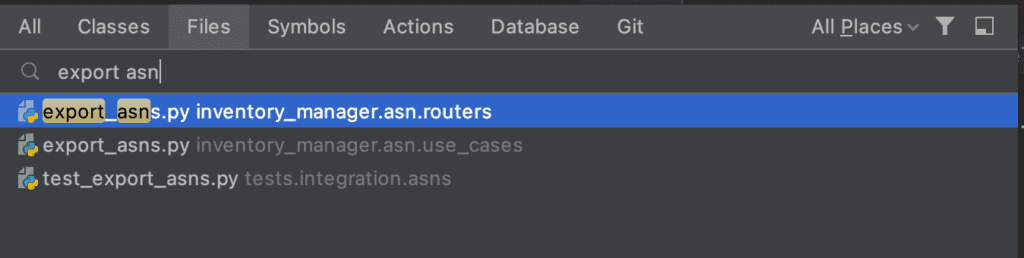

We almost stopped using the editor’s find tool; we relied on file filtering.

Feature Modularity

The use case-driven approach promotes decoupling between use cases. Since it helps to spot shared code between them, it’s less likely that you make that mistake.

Organizing codebases by use case is recognizing the reasons why the app exists. Use cases are your app’s units of work. Once you start taking advantage of that, you can identify features, sub-domains, and bounded contexts. This can help to create microservices and/or split work by teams if it makes sense.

Another by-product is straightforward feature flagging: each use case is represented by a class or function that can easily be swapped by another. You can manage that using conditional dependency injection of use cases.

Self-Documenting Code

Recall that each use case only needs a few injected dependencies. This makes tests smaller (fewer mocks) and easier to read. Knowing what each use case depends upon is also implicit documentation. When comparing this approach with a big hub/service with dozens of dependencies, it’s clearly better.

DTOs, errors, request/response models, and serializers are kept together with their use case (in the web or the domain facet). This contributes to documentation because context provides meaning. It also helps prevent technical hotspots.

The resulting app screams about its intents through a set of use cases. It clearly communicates what their clients can expect such as a restaurant’s menu telling the guests what they can order. Every newcomer can quickly learn what the project is about. Codebases become more about the user.

Fixing Existing Hotspots

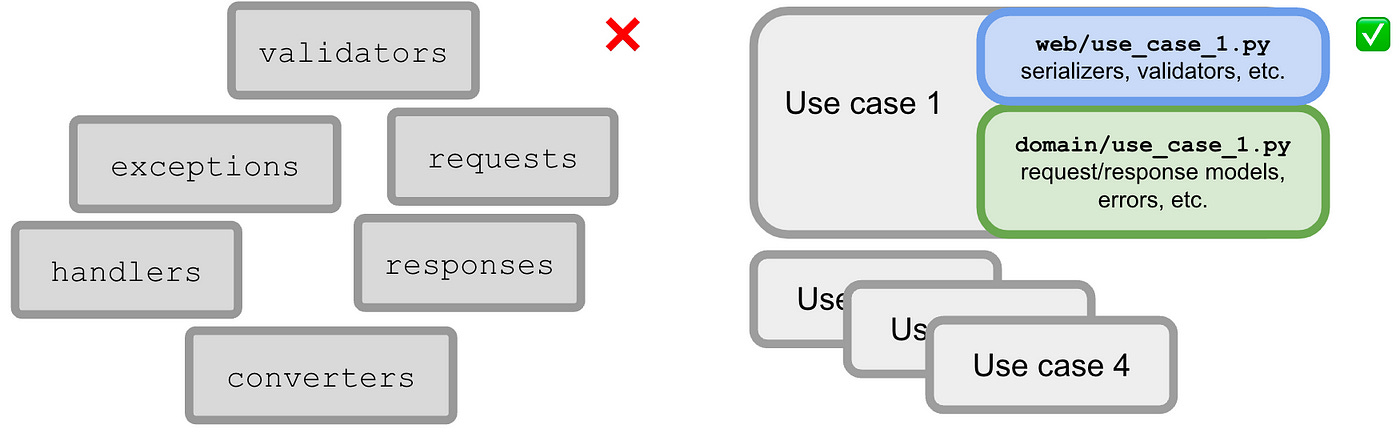

Most projects you deal with are not greenfield and present lots of code hotspots. Big bang refactorings are never a good idea. Baby steps will keep the process safer. Where to start? Focus on complex files that are constantly changing.

A quick and language-agnostic way to identify code hotspots is running:

npx code-complexity . --since 6.month --limit 8 --sort scoreYou can run it regularly and observe its evolution.

A good trigger to refactoring is picking a use case that you keep bumping into. To do it, start by isolating its tests. You may need to make them more high-level and less coupled with implementation details — resorting to testing patterns may help. Armed with the use case tests, it’s easier and safer to isolate the web handler and the domain use case. Don’t refrain from duplicating code to achieve use case modularity.